A story is told of a man who stopped attending his usual synagogue and was now frequenting a minyan in another synagogue. One day he happened to bump into the Rabbi of his previous synagogue, and the rabbi asked him where he was praying these days. The man answered: “I am praying at a small minyan led by Rabbi Cohen.”

The rabbi was stunned. “Why would you want to pray there with that rabbi? I am a much better orator, I am more famous, I have a much larger following.”

The man replied: “Yes, but in my new synagogue the rabbi has taught me to read minds.”

The rabbi was surprised. “Alright, then, read my mind.”

The man said: “You are thinking of the verse in Psalms, ‘I have set the Lord before me at all times.’”

“You are wrong,” said the rabbi, “I was not thinking about that verse at all.”

The man replied: “Yes, I knew that, and that’s why I’ve moved to the other synagogue. The rabbi there is always thinking of this verse.”

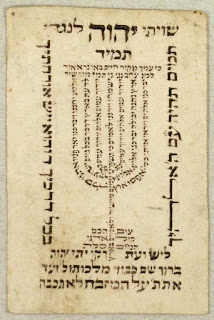

Indeed, the authentically spiritual person is always striving to be mindful of G-d’s presence throughout his or her day. Perhaps this is the reason that this verse from Psalm 16 is written above the ark in many synagogues. “Shiviti Adonai Lenegdi Tamid” — “I have set the Lord before me at all times.”

There are a number of interpretations of this verse from Psalms. Some believe it means we are being asked to contemplate Divine Oneness at all times. Others think it means we are to keep in mind that everything we see in the natural world, every aspect of reality, is, in effect, an expression of the Divine Name. Still others understand the verse to mean that we should meditate on the letters of the Divine Name of G-d, Yu- Hey-Vav-Hey, at all times.

If we do the latter — if we meditate on the Divine Name — what do we learn? This four letter name of G-d, consisting of the letters “Yud, Hey. Vav Hey,” is called the Tetragrammaton. When rearranged, these letters form the primary words used to express “time” in Hebrew. “Haya” means was; Hoveh -means is; and “Yiheye” — means will be. You may recognize these words from the prayer Adon Olam — Hu Haya, hu hoveh, vehu yiyeh betifarah. This teaches that G-d is present in every moment in time. G-d is present beyond time.

When Moses heard the name “YHVH” at the burning bush, he did not hear the word “Adonai” as we pronounce it. He did not hear the name “Jehovah” as German scholars pronounced the tetragrammaton. He did not hear the name “Yahweh” as is taught in our public school social studies curriculum. As Rabbi Arthur Waskow writes, “If one tries to pronounce it, what comes is simply a Breath. Its brilliance as a Name of God is that it alone, Breathing alone, is “spoken” in every human tongue….. And not only is it a language of humans but also of all forms of life — grasses, trees, frogs, birds, and leopards .………..As the Siddur teaches, “Nishmat kol chai tivarekh et-shimcha” — The Breath of all life praises your Name,” because the Name [of G-d] is the Breath of all life. In that phrase, “our God” does not mean the Jews’ God, nor the humans’ God, but the God of all living, breathing beings”.

The rabbis of the Talmud who taught us to pronounce this name of G-d, this breath-name — when we read it in our prayer books or study it in our texts — as “Adonai”. This means, “my Lord”. Many Jewish people today use the term “Ha-shem”, when referring to G-d. “Ha-shem” means “The Name”. Others refer to G-d as “HaKodosh Baruch Hu ” when speaking, meaning, “The Holy Blessed One”. But these are circumlocutions, and substitutions for the real Name of G-d, which is considered too sacred to pronounce — IF we knew how to pronounce it!

Moses, who heard the name pronounced at the burning bush, passed the pronunciation of G-d’s name down to Aaron the High Priest, his brother. And Aaron’s family passed it down through the generations of High priests that were in charge of worship in the Temple in Jerusalem. For it was during the sacrificial rites of the Ancient Temple, during the ritual confession on Yom Kippur, and Yom Kippur alone, that the Name of G-d was uttered by the High Priest. On that day the High Priest made confessions three times, humbling himself before G-d and asking for forgiveness- first for his own sins and the sins of his household, then for the sins of his fellow priests, and then for the sins of the entire people of Israel. When the High Priest pronounced the “shem meforash”, the explicit Name of G-d, all of the people at the Temple in Jerusalem would hear it and would bow and prostrate themselves and calling out “Barukh Shem Kvod Malkuto Le-olam Vaed”- praised be G-d’s glorious sovereignty forever.“

However, with the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in the year 70 CE brought to an end the sacrificial system of worship. With a service no longer taking place in the Temple on Yom Kippur, the pronunciation of “The Name” was eventually lost. Today, no one knows for certain how to pronounce the Name.

Let’s continue to meditate and reflect on this four letter name of G-d. The first letter of the Name of G-d, Yud, has the numerical equivalent of “ten”. This corresponds to the date of Yom Kippur, the 10th of Tishre, as well as the ten days of repentance. Moses also brought down the 10 commandments from Mt. Sinai on Yom Kippur. In Kabbalah, there are ten creative forces, or sefirot, that stand between G-d and our world. It is through these forces that G-d rules the universe, and it is by influencing them, through the practice of mitzvot, that human beings can precipitate G-d’s blessings to our world from G-d’s abode above.

The second letter, “Hey” has the numerical equivalent of “five”. This corresponds to the five prayer services on Yom Kippur. On weekdays we have three services, on Shabbat and holidays, four. Only on Yom Kippur do we have a fifth service of the day, the Neilah service . Kabbalistically, the letter hey, five, represents the 5 levels of soul of which the fifth level, or yechida is the highest one. By this we mean that the soul, our truest or essential self, is more accessible on Yom Kippur than on any other day of the year.

The third letter, vav, has the numerical equivalent of “six”. This corresponds to the number of divisions in the Torah reading on Yom Kippur morning. In Kabbalah, this number represents the six emotional attributes that exist within each of us — anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. On Yom Kippur we ask forgiveness, from G-d and our fellow human beings, for our mistakes and flaws related to these six emotions.

The final letter of G-d’s name, “hey”, corresponds to five. This represents the five prohibitions of Yom Kippur — eating, drinking, bathing, wearing leather shoes, and sexual relations.

Why these five restrictions? Many answers have been put forth, including “because the Torah says so.” But I think these restrictions are there to focus us on the task at hand. Although we cannot pronounce the name — it is too holy– we know the name, we can stand before the Name, and thus we can address G-d intimately — by name, as it were. With this great privilege comes responsibility. No one can ask forgiveness on our behalf from G-d but us. No one can be an agent for us in asking forgiveness from our fellow. Repentance is in our own hands.

Our services are integral in setting the mood and tone for repentance. Our liturgy can be an excellent guide in our process of teshuvah. The rabbi and the cantor and the choir can inspire self-reflection through their words and music. But on Yom Kippur, each and every one of us stands before G-d, alone, as individuals, to acknowledge our sins and ask forgiveness. Serious business!

Consider this parable: A person tries to cut down a tree with a dull edged saw. He works very hard, but makes little progress. A passerby sees this and asks, “Why don’t you sharpen your saw?” The person responds, “I don’t have time. I can’t stop working. I have to cut down this tree”. The passerby says, “But if you would stop working for a few minutes to sharpen your saw, you would actually save time and effort, and you would be better able to accomplish your goal!” The person replies, “No, I don’t have time to stop working. I must keep on sawing.”

The person in this parable represents us. We have the right tools to look at our lives and recognize where we need to improve, but those tools are too dull. We spend a great deal of energy trying to change, but we are not getting the results we want because we are using the same blunt instruments. We need to stop and think more clearly about our goals and how we are going to achieve them. Yom Kippur is a day when we take the time to sharpen ourselves spiritually. On Yom Kippur we cast away the toothless saw that we are using to do our spiritual work. We sharpen ourselves spiritually through fasting, through abstaining from pleasures, through forgoing luxuries symbolized by leather shoes. Once in this state we can better face our limitations, acknowledge our wrongdoings, atone for our transgressions and return to our spiritual core.

If, instead, we allow ourselves to check our email, see what is on Netflix, pause to have a snack, or do some shopping online we will lose our focus and squander the opportunity to accomplish the spiritual work that this day demands of us.

We live in a do-it-yourself world. We go on YouTube to learn how to fix a leaky faucet, put up our own shelving or lay down a tile floor. We bank online, do our own investing and are more involved in our own health care. The same do-it-yourself attitude needs to be applied to repentance in particular and to Judaism in general.

We may not all be like Rabbi Cohen in the story I told at the beginning of this sermon, always thinking of G-d, either directly or in the back of our minds. But let us strive to be more like Rabbi Cohen on this day, on Yom Kippur, the Holiest Day of the Jewish year. On this day, this one day of the year — HaYom! — a day when we do not eat or drink, a day when we abstain from pleasures, a day when we do not work — on this day let us all try to put our relationship with G-d front and center and to set G-d before us at all times.

Gmar Chatimah Tovah

May You Be Sealed in the Book of Life for the coming year.